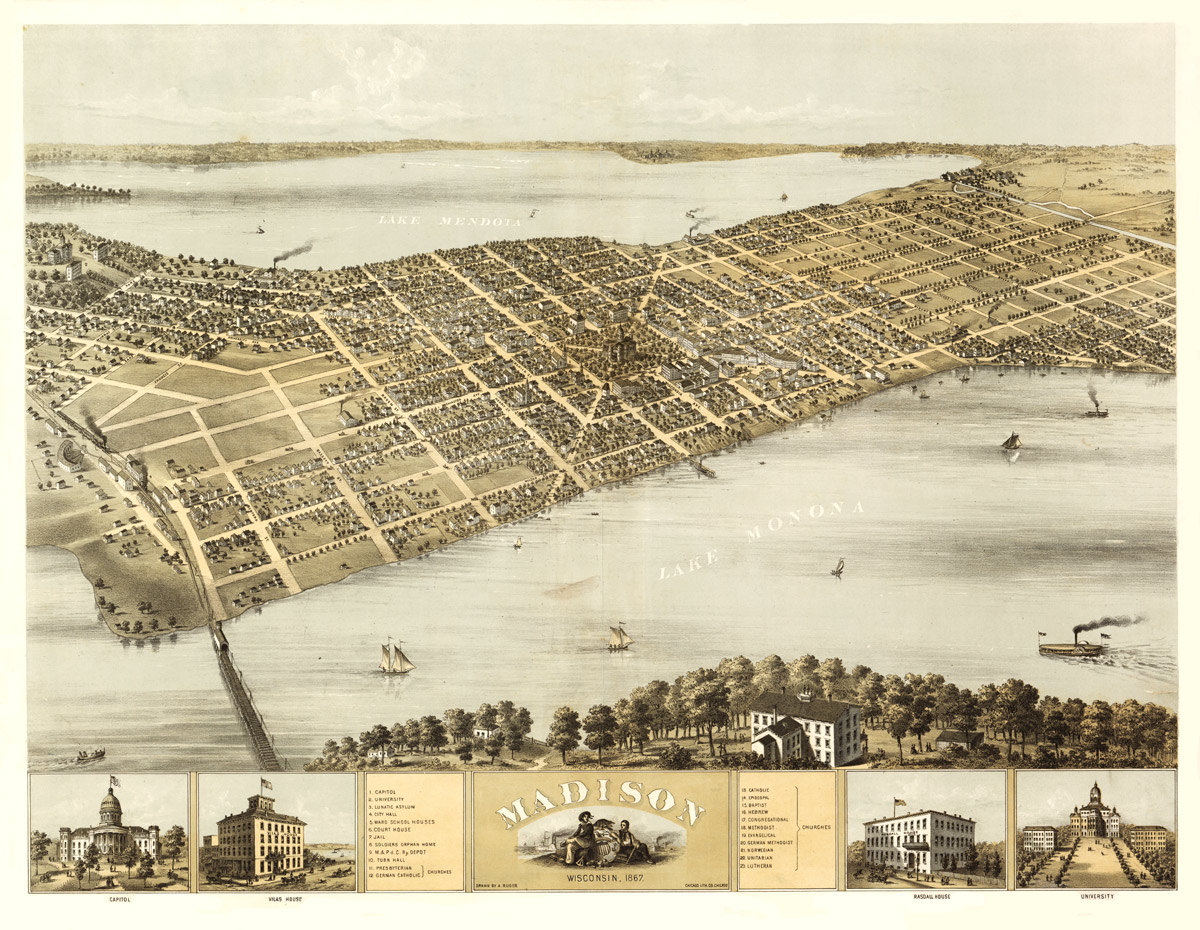

In my last blog, I wrote about big changes happening in Madison over 150 years ago during the “Village Decade”. Among other things, I observed the similarities between those boomtown years and the growth and change we’ve seen in Madison during the past few years. While there are many glorious moments when a city prospers, there are also inevitable growing pains. In part two of this topic, I’ll share some interesting facts and challenges that were part of city life in the 1850s.

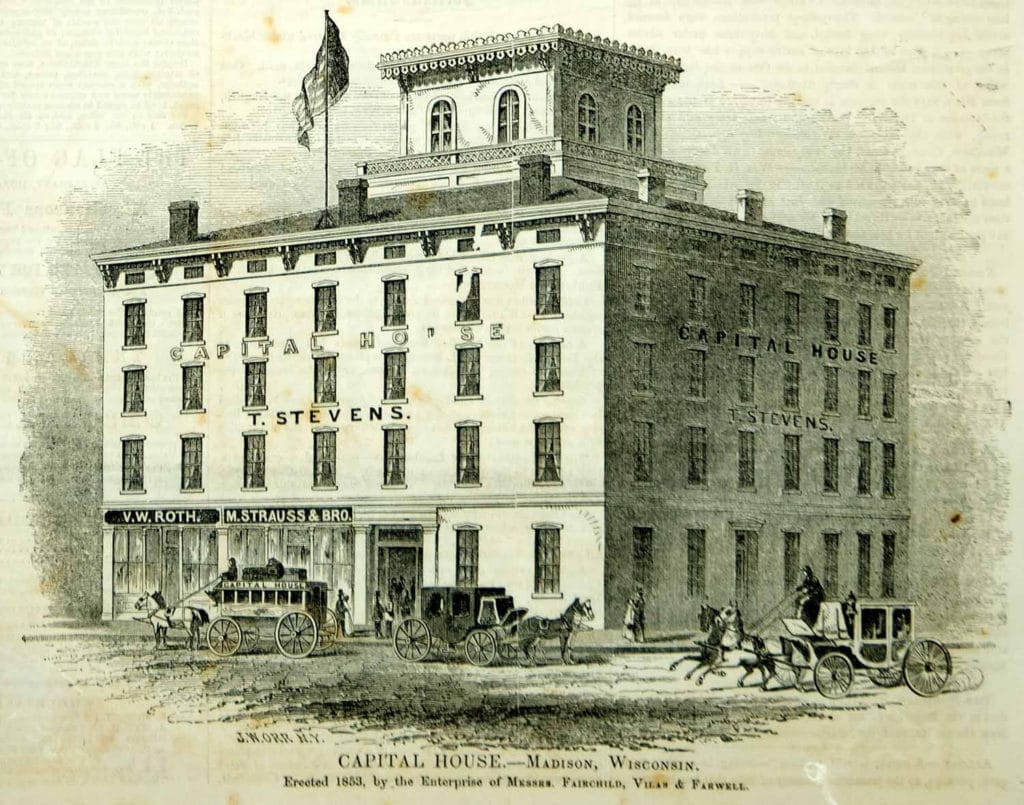

To call Madison a village at the beginning of this period of prosperity was likely accurate according to standards at the time. But Madisonians aspired for something more – to be designated as a “city”. Becoming a city meant you were in the league with already great American places like New York and Washington. With a thriving newspaper, a luxury hotel, fancy carriages, cabs, and gas streetlights, Madison certainly had acquired the “things” that made a city in the nineteenth century.

Besides the cache of calling itself the “City of Madison”, there were also practical, if not political, reasons for Madison to become a city. The village of Madison enacted a charter in 1846 but it soon found serious limitations on the ceiling for property tax rates. Even with other revenue sources like liquor licenses, fines, and special assessments, Madison lacked enough money to pay for fire engines, schoolhouses, a new cemetery, roads, and sidewalks. The charter also had jurisdictional issues with the town of Madison as well as unequal representation on the county board. To overcome these challenges, village leaders requested a city charter, eventually granted in 1856, for approval by the legislature. On March 7, 1856, the bill was signed into law and Madison officially became a full-fledged city.

As is true today, running a city also includes its fair share of problems, most of them caused by not enough money. One of the most talked about issues during the village decade was public schools. With Madison’s dramatic growth came too many schoolchildren and not enough schoolhouses and teachers. A twenty-by-forty-foot brick schoolhouse built in 1846 was still the only schoolhouse ten years later. Only a quarter of the school-aged children could squeeze into the little brick schoolhouse, so other students attended school in churches, a part of a carriage factory, and other various places around town. Besides the lack of space, teachers were also in short supply with a teacher-student ratio estimated at 1:125. Sadly, despite efforts to fund schools, very little progress was made during the village decade despite the prosperity that built fine churches, a Court House, and a costly jail.

Other problems during the village decade were streets and sidewalks. Dirt streets were either a rutted, muddy mess during rainy weather or very dusty in dry weather, making it unpleasant to breathe. Residents also used streets for free storage, so there was often an unsightly assortment of boxes, barrels, piles of wood, hay, ashes, and rubbish. Sidewalks at the time were the responsibility of the property owner to build. Very few did so, leading village trustees in 1855 to take responsibility for sidewalk construction.

Public sanitation and disease were a major issue during this period as in other US cities as well. Simply put, people just didn’t take sanitation seriously. Garbage and slops were often dumped in the streets, dead animals were many times allowed to decay wherever they dropped, and offal from the slaughterhouse was sometimes thrown in the lakes. Whether it smelled or looked bad, the only issue that caused the citizens to take action was disease. There were frequent cholera epidemics in the late 1840s and early 1850s, which led to quarantines, purifying streets and yards, and draining polluted standing water. Attempts were made to bring in piped water, which finally became a reality 30 years later.

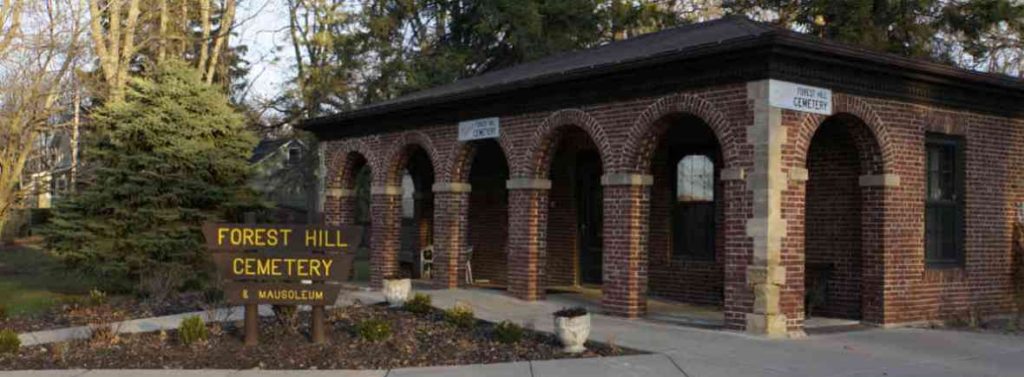

There were also some more light-hearted challenges as Madison became a city. For one, the village cemetery, located at today’s Orton Park off Williamson Street, was too crowded and overrun with cows. Soon after the city charter was enacted, the common council established a new cemetery at Forest Hill, still there today near West High School.

One other challenge I found entertaining was described by David Mollenhoff in one word: ruffianism. As Mollenhoff writes, “Madison’s remote location and rapid growth combine to attract a very rough class of people whose drinking, gambling, fighting, brawling, and swearing were notorious.” Newspaper editorials, settlers, and visitors described Madison as a place with “haunts of vice” and where “the best men in the state are sots”. A saloon census in 1853 discovered there was one saloon for every 90 residents. The rowdy behavior and drunkenness tempered somewhat as city leaders made various attempts to dry out Madison and fine anyone who sold liquor.

One other challenge I found entertaining was described by David Mollenhoff in one word: ruffianism. As Mollenhoff writes, “Madison’s remote location and rapid growth combine to attract a very rough class of people whose drinking, gambling, fighting, brawling, and swearing were notorious.” Newspaper editorials, settlers, and visitors described Madison as a place with “haunts of vice” and where “the best men in the state are sots”. A saloon census in 1853 discovered there was one saloon for every 90 residents. The rowdy behavior and drunkenness tempered somewhat as city leaders made various attempts to dry out Madison and fine anyone who sold liquor.

I hope you enjoyed this venture into a small part of Madison’s history and found it as intriguing as me when you look at our present-day city life. Compared to other places around the globe, Madison has a very short history, but as the introduction to Mr. Mollenhoff’s book states, “we are just beginning to understand the power of local history to enhance our understanding of ourselves, our cities, and our culture. It is, after all, this stratum of history that touches most of our lives most of the time.” I am grateful that we have this history recorded from over 150 years ago and that Madisonians have worked tirelessly to preserve important buildings and parks as well as public policy and city resources. In the year 2166, 150 years from today, I hope we will look back at present day with the same appreciation for all the triumphs and challenges it takes to make a great city.