“No period in Madison’s history produced so much change so quickly.” “A heady, almost uncontrollable prosperity reigned. The number and scope of new developments were dizzying.” “If Madison did not possess the full style and dignity of a city, people thought it was rapidly moving in that direction.”

Whether you’re a resident or occasional visitor to Madison, these quotes might make you think about the last few years in Madison. Our downtown Capitol Square is full of exciting new restaurants and shops. Johnson Street just west of State Street features new high-rise apartments and hotels squeezed into city blocks where little one and two story residences and businesses once stood. Similarly, East Washington is also booming with high-rise apartments and restaurants, displacing abandoned buildings and car lots. Breese Stephens Field is alive again, and University Avenue is full of beautifully designed new buildings supporting all that’s happening at UW-Madison.

Oddly enough, though, these quotes come from the introduction to chapter two of David Mollenhoff’s book Madison: A History of the Formative Years. The chapter is titled “The Village Decade: 1846 to 1856”. I thoroughly enjoy reading about the village decade because so much happened and it was around the same period when our home was built. But the chapter also fascinates me because I see so many parallels between those ten years and current events, not just in Madison, but in many growing U.S. cities.

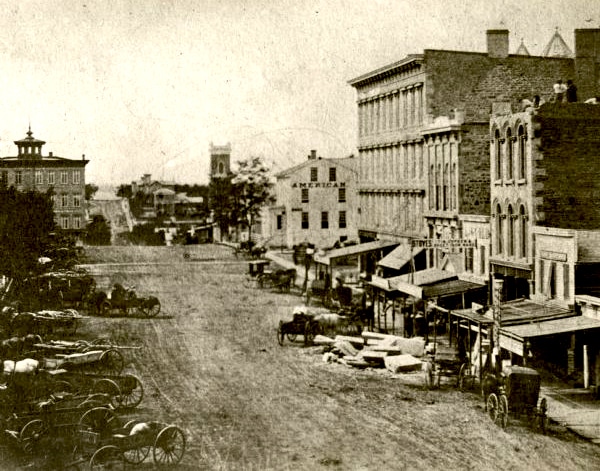

credit: Wisconsin Historical Society, Image ID-2650

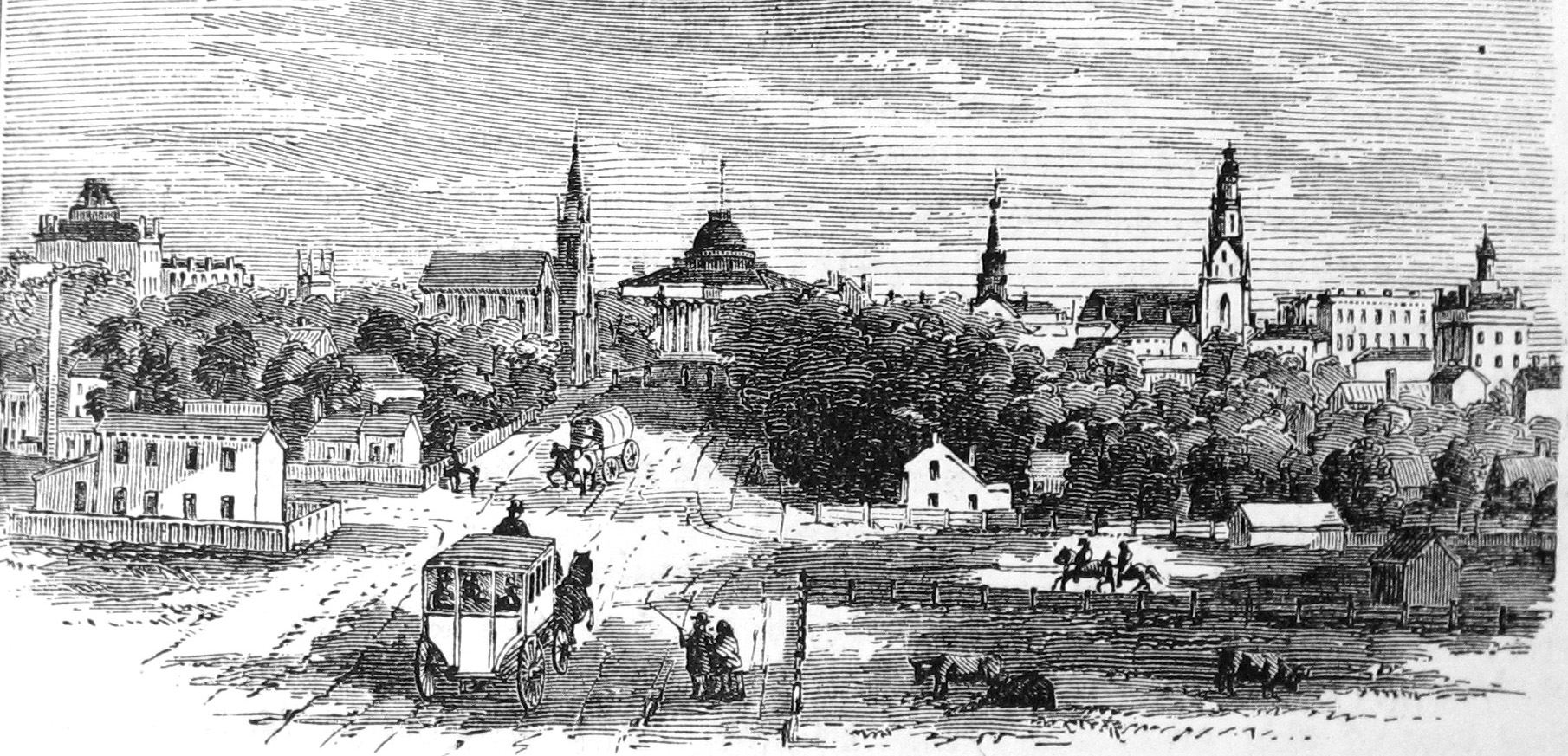

Mr. Mollenhoff begins the chapter describing the Farwell Boom when Leonard James Farwell came to Madison from Milwaukee in 1847 and was a champion for the growth of the area. Like others, he realized the potential of Madison’s location at the center of a large fertile area with no competing towns for miles around as well as its beautiful setting and its designation as the territorial capital. A year later, in 1848, Madison’s future became even brighter with three significant events: Wisconsin became a state, Madison was made its permanent capital, and Madison was made the home to the University of Wisconsin.

Farwell’s vision and leadership touched our city and state in many ways. In 1852, he became Wisconsin’s youngest governor at the age of thirty-three for a two-year term, and his accomplishments during this time were amazing. Among them, he abolished the death penalty, created the state banking system, built Mendota Mental Health Institute, and created the State Commission of Immigration to actively encourage migrating Europeans to settle in Wisconsin, an idea subsequently copied by other states.

Even as governor, Farwell didn’t abandon his dedication to Madison. During the 1852 and 1853 construction seasons, Farwell set a crew to grade East Washington Avenue from Blount Street to the Yahara River (a little over one mile). On top of the grading, the crew built a double plank road, Madison’s first form of paving, and to finish off this grand project, 6,000 maple and cottonwood trees were planted along the sides of the avenue. While governor, he also led investment groups that put up the Capital House, one of the fanciest hotels in the state, and the prestigious commercial building called Bruen’s Block, which included the Wisconsin State Journal among its tenants. At the corner of East Washington and Pinckney Street, Bruen’s Block stood where now is the well-known glass building housing US Bank as well as the popular restaurants L’Etoile and Graze.

If Farwell’s many accomplishments weren’t enough, the village decade also brought another momentous change: the arrival of the first railroad in 1854. As Mollenhoff states, “to have a railroad pass through town was regarded as a prerequisite for urban success.” Canals were limited and roads were unreliable, but a railroad brought goods and people, regardless of weather, catapulting any community into major growth and progress.

To celebrate this historic occasion, Madison does what it does best – it threw a party. Everyone in town was invited and 2,000 people flocked to the depot on May 24, 1854 to see a steam engine – a marvel of modern technology – cross Lake Monona into the village. Following the ceremony to welcome the train, the crowd returned to Main Street where they celebrated with barbequed steers, chickens, and ducks. It was undoubtedly one of the most unforgettable days in Madison’s history.

Following the arrival of the first train, life in Madison changed almost immediately. Just days after the railroad opened, up to thirty-car trains carried Madison wheat to Milwaukee. Travel through town doubled that summer and housing starts dramatically increased. The population exploded from 600 people in 1846 to 9,000 just ten years later – an increase of 1500%! The population growth pushed development into Mansion Hill, Fourth Lake Ridge (our current Tenney-Lapham neighborhood), Third Lake Ridge (today’s Williamson Street area), around the railroad depot (now the Bassett neighborhood), and along State Street.

Undoubtedly, the Great Farwell Boom and the village decade of 1846-56 laid the foundation for what Madison has become today, its impact still notable in many ways throughout the city. It makes me appreciate what I see around me when driving and walking through our downtown area.

As many of us know, though, growth comes with its share of problems and sometimes quirks unique to a city. In my next blog, I’ll share some of these as well as Madison’s notable rise to officially becoming a city.